Arturo Ui, National Theatre of Kosovo Tringë Arifi Violence in the city. Violence in the people. This is the plan of gangster Arturo Ui, who in addition to a character in a play by Bertolt Brecht, is a character of our times, our politicians and those who govern us. Emptiness and decay manifest themselves in a moment when things do not go as expected by Arturo and his gang, slowly emerging into chaos. There is a lot of symbolism in the production, the last to be directed by the late Bekim Lumi. A scene in a bathroom, in which men sit on the toilet bowl sipping espresso, symbolises their comfort. This is followed by the complaints from the minority to the majority (the people) where they say `` why are they complaining`` ;`` why do you see crisis and why are the people not giving the cauliflower products while they are rotting? `` … They are sitting comfortably over the rot and misery they have created, trading in cauliflower then passing on complaints about not selling them. When some of his friends start to complain, to get out of that kind of comfort, Arturo's circle is narrowed further. The boss appears in the bathtub and two men scurry around him, then one comes and kills the other in front of Arturo - perhaps this scene shows the inferiority they have towards him, the will to commit more and more crimes to keep Arturo happy as he becomes the highest in the hierarchy of crime. After this macabre scene of murder disguised as suicide, the mafia talks about the corruption, while the old man appears as a business intermediary who is threatened. The whole scene is accompanied by music. Tom Waits' November is used in the face of crime, like Beethoven's 9th symphony with which the Nazis had committed crimes against humanity, and so they sing and dance like crazy people. As violence echoes across the city and humanity, Arturo devises another plan to destroy the courts in which the perpetrators are supposed to face justice. The culmination of the crime comes when his friends have become worried about Arturo as he comes second and kills the two friends who were in trouble for him. He is afraid of his own being. The old man addresses Arturo about the glory. He says that it is not won by force - and so the old man is also killed. Corpses appear in bathtubs. The first corpse is unveiled and resurrected. He rises and gives a speech: "You killed yourself when you killed me." Then the unconscious man begins to talk about violence, robbery and murder. He talks about the faith, about the will of the old man, the thanks he gave him in the will - though we do not see the will. When Arturo asks for votes on who is in his favour, he says those who are not in favour are necessarily against me. His only two remaining friends raise the hands of the dead from the grave as if they were voting, saying that everyone should be thankful. The irony is that only the two are alive and can vote, but his unjustifiable desire for power and crime makes them his two remaining friends lie and deceive him with votes, just as he likes to constantly lie to himself. Arturo appears again with an ironic speech about peace, protection of the city and trade, in which he says that no slander will stop him and he laughs like a madman. This laugh comes from not facing oneself, fear of oneself, a conclusion that drives him crazy. This is how the fate of a people ends and the scene closes without seeing the fate of this leader, but the being and the destruction towards this being are very well illustrated. The actors bring subtlety to their roles, an interiority is evident in every performance. Bujar Ahmeti, an actor of the new generation performs with the skill of a veteran. He takes the audience with him, walking us through the devilish mind of the character. Afrim Kasapolli, an actor of the older generation plays Dogsborough. He uses his interior a lot and masters the stage. The actors work well as an ensemble, as a team, clearly confident in the director and the concept. They fuse together. They become one. They evoke the passion, courage, and emotion of the characters, delicately drawing the relationships between the characters throughout the show. Author: Bertolt Brecht// Director: Bekim Lumi//Ass. director: Bashkim Ramadani // Cast: Bujar Ahmeti, Afrim Kasapolli, Afrim Mucaj, Labinot Raci, Faris Berisha, Valmir Krasniqi, Edon Shileku, Ismet Azemi, Ylber Bardhi, Kushtrim Qerimi, Shpetim Kastrati, Muhamed Arifi, Alban Rexhaj // Choreography: Majlajdo Gala // Music: Dren Suldashi // Stage Design: Mentor Berisha // Costumes: Alma Krasniqi // Tailor: Fadil Sahiti // Light Design: Mursel Bekteshi // Sound Design: Dren Suldashi, Avdi Gervalla // Stage Manager: Bajram Mehmetaj // Translation into Albanian: Robert Shvarc // Adaption into Gheg: Gazmend Berlajolli, Bekim Lumi // Organizer: Beqir Beqiri // Master Carpenter: Aziz Maloku // Carpenters: Rrahman Mehmeti, Hasan Buzaku, Fatmir Avdiu // Props: Xhemail Gllavica, Driton Musliu // Dressers: Fahredin Ahmeti, Linda Ahmeti // Make Up: Flori Hasani, Myrvete Tahiri

0 Comments

Balava, Theater Oda Agnesa Mehanolli What can two generations of women in the absence of men offer us on the stage? Dunja Matic's Balava wove together isolation and desire for freedom; courage and fear, love and dissatisfaction. The plot was a complex one. A mother of two daughters tries to keep them to herself by projecting on to them her own insecurities, vulnerability and the need to be loved and needed. She holds the ropes of the story. Her past has created a hole inside her that now seems to be filled only when she is accompanied by the only ones left that can ever love her. Played by Mirjana Karanović, the role was well-executed, a woman undefeated against a tragic fate, against the cold loneliness and against the big challenge of being a single mother. The formal dress, the hair fixed for a special evening, the posture, the way she talked, all these were perfect for the role. It was a performance of energy and commitment. Her sister, Tetka, played by Jasna Đuričić, was a character scarred by her own tragedy, who tries her best to reflect a spirit of joy and tranquility for her and the girls. She is the one trying to keep a level of normality until she will be the one that breaks down. The actress wore a spring dress, her hair fixed loosely and her careless body movements, that radiated warmth, were entirely different from her co-actress. All these differences only made the actress’s elegance more needed in the stage. The daughters, total opposites of each other, have different perspectives but the same purposes. One (Balava) desires to create happiness outside the house, with a Boy she met and the other, Babe, longs for a freedom far away from her suffocating mother, as a way to be happy. They try their best to get out of the house and live and enjoy their long lives; but Balava gets caught in an unexpected pregnancy and fears that the future she has created in her head is starting to fall apart. She experiences an unwanted abortion just when she made peace with wanting the baby, and despite her mother's claims of her to be an easy minded girl, she dares to confirm the opposite and run away from the house while trying to prove that she is the only one that can make the best decisions for herself. The actress Mina Obradovic represents a young character in the best supposed time of her life. She seems to have calculated all the right amount of joy, hope and saddens needed to intertwine in her character’s life. She performs with such an ease during the whole play, even in the most intense moments and is to be congratulated for her style of acting. The other daughter gets stuck there with her mother, and no matter how much she fights her and blames her for everything, she realizes that her is all she got, the same as she is all her mother got, that way she can't leave her alone and break her heart twice, after her father. Jovana Belović is careful to perform this character just as it is supposed to be performed; combining her father’s desire for freedom and her mother’s tendencies to be blocked. She was transparent, allowing us to see the wrecked world of the play’s character and she brought colour to the stage, to a world in which no colour exists. The set consisted of only four chairs lined side by side, showing a unity between the four of them, thus symbolizing that they have someone close even if they feel alone, that there is a space to be filled by them, even if the world is to small or to big to find them some place. The candle in front of them made me believe that in this house, there was some warmth, no matter how small. And however hidden, love is there, hope is still there and things will change, be that for good or just to make our characters understand that this all the best the universe can give them and maybe it’ s time to accept that. The dialogue flowed very smoothly. The jokes were delivered well, but sometimes the public (including me) laughed at them beforehand, since the subtitles were faster than the delivery. And that a shame, destroying the magic of these comic moments. But the real tragedy is the fact that all four of these women were closed in with so many walls, physically or mentally and none of them had the means to be free without losing a part of themselves. I was happy to have witnessed a play written by a woman, performed by women and visualized by a man, Andrej Nosov, as it demonstrates that the other sex has started to understand the female nature and its limitless capability to face the challenges and tragedies of a world that has only this to offer them. Author: Dunja Matić // Directed by: Andrej Nosov // Cast: Mirjana Karanović, Jasna Đuričić, Jovana Belović, Mina Obradovic // Composer: Draško Adžić // Stage Design and Costumes: Selena Orb // Stage Movement: Damijan Kecojevic  A.Y.L.A.N, City Theater of Gjilan Natasha Tripney The audience sit on the stage looking out a sea of empty seats. From this perspective they look like waves breaking on the shore. A rough red sea. Bodies flip flop across the seatbacks, storm tossed, both waving and drowning. Jeton Neziraj’s text takes the form of a minimal series of numbered micro-scenes, Brecht on espresso. It’s a slim play and, as such, a director’s playground. Blerta Neziraj takes this challenge and she runs with it. From this frame, she has woven an incredibly vivid and inventive piece about the plight of refugees forced to make perilous life-threatening sea crossings in search of safety. The play is ostensibly a comedy about Roccalumera, a Sicilian town where nothing of note ever happens. It’s starting to grind people down, the lack of action. Even the cat is depressed. A few refugees would at least liven things up, just like in Lampedusa. When they come across a body on the shore, they are ecstatic; even though, in all likelihood it is an Italian, they dress it up in a niqab. Blerta Neziraj takes what sounds, when spelled out like this, like the most caustic of comedies, as the inspiration for a series of incredibly striking stage pictures. Together with choreographer Gjergj Prevaz, she turns the inverted world of the theatre into a space of play and of dreams. The actors, dressed in funereal black suits, clamber across the empty seats; they stride from row to row. The rows of crimson seats become rolling surf, waves under which a body can sink. The lighting design by Yann Perregaux completes the transporting effect. He phosphoresces the theatre, plunging it into flickering darkness, creating an indoor storm. He pulls us down towards the seabed.

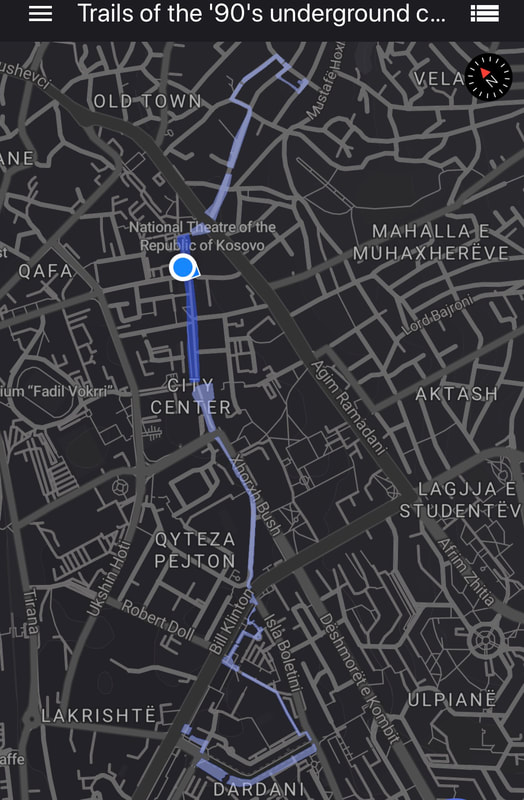

The cast work well together, whether zipping themselves into body bags or forming a chorus. Originally staged at the City Theater of Gjilan in 2019, the production was screened during the showcase due to the indisposition of one of the actors, but its power was not diminished. The way in which the space is used, with the actors and audience in opposite places, an inversion of the normal way of things, is the perfect representation of a world in which people fleeing warzones, people desperate enough to try and cross turbulent waters in a flimsy dinghy with their children in tow, are demonised, are seen as people to fear. Though less than an hour long, the production executes several deft tonal pivots, from comedy to horror and back again; only in the end does it slow down and unveil the image of Aylan Kurdi, a three year old boy, face down in the sand, dead. It confronts us with this image that briefly horrified the world but all too quickly became absorbed into the public imagination, one more picture at which to sigh and shake our heads. The last stretch of text is an act of re-humanisation, a poetic reminder that this is not just a powerful photo but someone’s child, a boy who once played and smiled, a life cut appallingly short. Author: Jeton Neziraj // Directed by: Blerta Neziraj // Ass. Director: Avni Shkodra // Cast: Aurita Agushi, Ernest Zymberi, Kushtrim Qerimi, Tringa Hasani, Gani Rrahmani dhe Alban Shahiqi // Stage Design and Costumes: Mentor Berisha // Choreography: Gjergj Prevazi // Music: Tomor Kuci // Stage Technicians: Mejdi Hoti, Haki Aliu, Fehmi Hoti // Organizer: Raif Haziri // Light Design: Yann Perregaux // Lightning Technician: Fatmir Halili // Sound: Florim Gagica // Props: Suad Berisha // Dresser: Bahrije Kurtalan Trails of the ‘90s Underground Culture - an audio walking tour Fatlinda Daku Everything starts in Dardania. And by everything, I literally mean everything. I have my iPhone and my earphones. I have downloaded the Echoes application. I am ready to listen. He lives on the 7th floor. He and his friends are playing outside. His mom stares through the window. Your mom does that too right? Or at least she used to do when you were young and went outside to play. Everything looks normal. He is eighteen and by the law, he is considered a grown up person. He has had his first sentish dance. He and his friends go to the pubs and talk and dance and enjoy the music. Just like I do, and you also. But this guy lives in 1998. And we are from 2020. In Kosovo. And there are two Serbian policemen who come sometimes and shout down the bars. The Albanian bars. They asked him one day if he would serve in the army. He responds that he will because it is his civil duty. That’s what others told him to say to them. I observe. I check my phone. I am being reminded to continue walking until I reach the end of the highlighted area. It’s a bit messy to figure out this application, but I am managing somehow. I look around. We are at Santea now, or as it was called on the 90s “Hani i dy Roberteve” A place when artists, journalists and philosophers used to meet and discuss everything, from Kosovo to Shakespeare. He has his Theatre Directing classes there. I keep walking with him inside the corridor. There was a protest by Albanians in the morning. Metallic things were flying around. He couldn’t finish his espresso. He had to go. It’s 24th March, 1999. They planned to meet with Adriana today. She was an actress, a good friend of his. With her mother they have arranged to go to Tetovo because it was safer there. We hear the noise of bullets. We learn that Adriana was killed inside this pub. I am sad. I think about Adriana while I keep walking through the highlighted area. I think of how many theater performances and films she would play in if she was alive today. I think of the contribution that she would give to the theater of Kosovo. As a woman, as an artist, as a hero of abnormal times. I keep walking. Now, he is talking about Nesha, a tall policeman, a Serbian guy. About the onion in his pocket during the protest. About the list. About the fact that he misses the main streets of Prishtina. About his first role in public space as a Serb. About his privilege of having a satellite television at home. About the Italian journalist who came to Prishtina and couldn’t believe his eyes. About Faruk Begolli, Enver Petrovci and his other professors. About many other things. I keep walking and listening to his stories.

The 90s are not black and white for me anymore. I think about how important these kinds of stories are. Personal ones. When young people were trying to be normal young people in abnormal times. I think about why there are not many stories like this being told to us. Why there is no recognition for these people as heroes too. Heroes of abnormal times. This was on my mind during the whole walk. I look at him now, at Florent. He is not eighteen anymore. It’s 2020. We just arrived at Theatre Dodona. The walk is over. A new theater show is about to begin… ‘You have discovered a perishable treasure, and it is imperative to share it with other people before it fades… ’ Irving Wardle

Over a five-day period, participants will attend workshops exploring the purpose of criticism – both as a space for analysis and debate, and a creative act – and the process of writing a theatre review. There will be the chance to discuss different critical approaches, style, structure, and form, as well as the changing role of the critic in an evolving media landscape. With the reduction of space for arts coverage in most mainstream media outlets, we will look at the practical realities and responsibilities of working as a critic today and discuss the benefits of a healthy and rigorous critical culture to Kosovo’s artists and audiences. |

Kosovo Theatre ReviewsReviews and creative responses to theatre productions in Kosovo Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed