Photo credit: Atdhe Mulla Audience by Vaclav Havel, Theater Oda - another viewFatlinda Daku

What would an Investigator want at the theatre? You can find them everywhere. Especially in important positions. As administrative employees in the municipality, tired of looking at the clock to see when the working hours are ending. As principals of schools, gymnasiums and universities watching videos on Facebook inside those old brutalist-style brown offices that smell like cigarettes. As government employees who return emails 100 times with numerous miniscule requests for improvements to the documents that you send to them because they have nothing else to report to their superiors. (Ironically, of course, these emails contain a lot of spelling mistakes). They usually belong to a political party. They are 40-50 years old, in some cases even older. They're married. Some of them dream of cheating on their partners. Some of them even do. You usually have to go to them for a document. But it does not happen often that they come to you. Especially in the theatre. In Audience by Vaclav Havel, the investigator in question has ben sent by his superiors at the police station to investigate a complaint by the director of a theatre. The events of the play take place in the actors' dressing room, an old room with minimal facilities. The director of the theatre tells the investigator that they have called for funds many times to renovate the theatre, but no one cares because, according to them "up there", they have more important things to deal with than that. An awkward conversation takes place where the inferiority and superiority of the two characters dance over the sounds of their words in a way that is clearly noticed by the audience. The inferiority of the theatre director and his fear reminds me of the main character in Franz Kafka's The Process since he does not know what they have accused him of and what will happen to his fate. The investigator feels superior to the director in this because he knows that he has him in his hands, what with all these new laws and amendments and regulations, which if the investigator wanted (with his interpretation) he could use to send the director to prison immediately. The investigator also feels inferiority to the director's intellect and the work he does. The investigator understands deep down that he knows nothing. But knowing it and saying it out loud are two different things. Therefore, to fill this gap, he begins to show the director how he knows everything about the theatre. How he read Stanislavski's system, which according to him is the Qur'an or the Bible of the theatre. How he is not like other investigators, because he studies, analyzes and does in-depth research before taking a case and how he does not type with two fingers like his colleagues. On the other hand, the Theatre Director knows he has done nothing wrong. But he also grasps that this is not enough in this country and continues to be scared. He asks the investigator if he came because of the new ballet competition. The Inspector does not tell him and continues to hold him as a ‘hostage’ in this nerve-racking conversation. Who is Rozi? There is a third character, the actress Rozi, but the audience does not see her. We just hear her voice, often crying, laughing, singing and reciting. "She is an unpredictable actress," says the theatre director, which is why everyone loves her. Apparently, the investigator is obsessed with her. He gets excited when he finds out she is there, in the theatre. He exaggerates her appearance in front of the Theatre Director, considering her as an almost mythical creature. He knows some of the roles that she played. He praises her, but also objectifies her in the most vulgar form. Then he asks the director how he can meet her. What role will she play? What is she doing now? And many-many other questions. The Investigator also finds drugs in Rozi's cosmetics in the dressing room, but when he found out that they were hers, he doesn't take the issue further. He even seems to soften with the Theatre Director when she is mentioned. Rozi serves as a distraction. As a distraction from the conversation for the Director. And as a distraction from the boring nonsense of his life for the Investigator. The statement This dialogue must come to an end. The Director is in a hurry and can’t wait for it to be over. The Investigator goes to the bathroom to see Rozi on stage and tells the Director to write his own statement and then, only after that, he will tell him why he came here. The Director is confused. He starts to write, deletes, writes, deletes and repeats the same things again. He fears that his words will be misinterpreted and will be used as evidence that he is guilty. The investigator returns and tells him that Niku, an actor, has complained that the Director has violated the regulations and has discriminated against him because he is not giving him roles in the theatre. The Director explains that no director will work with him because he is incompetent and does not know how to act. Discussions continue. The investigator listens, closes the file. Now, they are talking about the Ballet competition. The investigator has a daughter and her dream was to always be part of the ballet. And he wants her to be accepted in this competition that was opened by the Director. An a-ha moment! The conclusion of the play is clear demonstration of how forced nepotism works, the hypocrisy it creates and how much pressure is put on the people who are trying to do something good for their country by forcing them to compromise their values. The way in which the actors Shpetim Selmani, who plays the arrogant, but inferior Investigator and Dukagjin Podrimaj, who plays the ‘good guy’ Director who is only trying to do his job, conveys their feelings, to us, the audience, is fascinating. It was like the ugliest parts of realism were meeting the innocent parts of idealism. It felt like we were there, with them, in the dressing room, in complete silence, listening and waiting to see what will happen next, impatiently... In this way I found Agon Myftari's performance of Jeton Neziraj's play to be truly provocative, intense and relatable. In one form or another it makes us reflect on the compromises we may have made, with or without our knowledge. You may ask, how do we get out of this situation? I think we all know the answer to that. This performance was just a reminder of ‘’how’'. Author: Jeton Neziraj//Director: Agon Myftari//Cast: Dukagjin Podrimaj, Shpëtim Selmani

1 Comment

Photo credit: Atdhe Mulla Audience by Vaclav Havel, Theater OdaAgnesa Mehanolli

To think that time passes but so much remains the same is mind-blowing, right? The fact that a work of art, no matter how old, can be revived and put on stage and still make you feel the same as the first audience that witnessed it, is just… wow! I mean, Vaclav Havel wrote his play Audience in 1975, written to serve as a mirror of, or even a backlash against, the communist regime that existed in his country at the time. And to think, today, 45 years later, we still feel the need to put on such a play within the theatre scene of my own “democratic” country is just sad. Havel's play depicts a suffocating bureaucratic system that not only doesn’t contribute to the artistic wellbeing of its own country but is destined to prevent its progress, unless it under agreed conditions of course. This adaptation by Jeton Neziraj shows two men on opposite poles; a theatre director, trying to prepare a show for the premiere that’s supposed to be held in a couple of days and a man working for the system who has come to investigate seemingly baseless charges that turn out to be legitimate albeit absurd. The plot unravels itself in meaningless dialogues (that serve to make us bored) eventually reaching a point that says: What do you know? The truth is boring indeed! There is no conflict in this play. There is no special place to which the characters are trying to get. The play takes the form of a serious talk (with not such serious acting) about the serious problems of our governing system that sometimes intentionally makes space for a few little jokes just to keep us focused. There is a third character, but we never see her. The actress Rozi is an invisible character who from time to time takes the focus away from the other characters with her strange noises. I believe she is there to remind us that it’s a play we are watching. We can laugh a little, we can enjoy it. But she is also there to remind us what a key role in the decision-making of the bureaucratic world is played by the “female erotica” – element. To my mind, the whole point of this play is to allow us to understand the sad reality in which we exist. We need to see the dirty agreements that are constantly being made behind closed doors, even if it means contaminating the stage with such horrific truths. In fact, if it has come to this, than I am supportive of putting on stage plays with such intentions. Dukagjin Podrimaj plays the Theatre Director and Shpëtim Selmani plays the role of the bureaucratic guy. The personification of the director was executed perfectly by Podrimaj, making me feel each gram of his frustration, anger, tiredness, and hopelessness. He justified each and every word and action made by his character, to the point that the play felt a bit one-sided. Though Podrimaj convinces completely as the Director, alongside him Selmani is less persuasive as the Inspector. Or maybe it’s just me not remembering how bureaucratic types are around here, and Selmani is indeed doing the best to paint a portrait of such not-serious, grotesque and common guys like the one around here, in Kosovo. Watching this play feels like sitting in your favorite café. You find a good chair in a beautiful spot and your favorite waiter comes to take your order. You tell him that you trust his choice and with a very excited face he promises you the best drink, with all-natural ingredients. He disappears only to come back with a beautifully decorated cup and he tells you that it’s something original that he’s been working on these last few days. He assures you that it’s very delicious and you trust him just like all the other times when he proved it to you. But then, suddenly the boss shows up and he takes your drink, doesn’t let you try it, while coming to the conclusion that this is not what you ever wanted! And then he makes the waiter bring you a whole different ugly-tasting drink that contains “more than natural ingredients” that according to him are supposed to satisfy you. And what is left for you to do if things are going to work this way? To never come back there! This does not mean that I have come to the same conclusion as in the previous paragraph. It just means that, like a whole bunch of people in this country, we will soon get tired of drinking ugly-tasting drinks and we will rise to say no! No to bad theatre. No to bad governments. No to bad actors. Yes: to new opportunities, even if that creates more of everything I have mentioned. We are just going to have to keep on fighting. Author: Jeton Neziraj//Director: Agon Myftari//Cast: Dukagjin Podrimaj, Shpëtim Selmani In Five Seasons: An Enemy of the People, Oda Theater

Tringë Arifi The stories I’ve heard as a child were not just fairy-tales. These stories, that arose from love and in the midst of ruins, speak of a reality: the reality of post-war Kosovo. In Jeton Neziraj's play, the lord of construction, Meti, is initially presented as someone who suffered during the war, but he has a mission to build and reconstruct: ostensibly in the name of development. The Architect (played by Armend Smajli) also deals with the urban plans of the city; he has a love for his city, but he needs to deal with the legalities as well. The Architect works diligently for a city which is being ravaged by construction. A Journalist asks him for an interview about his plan, but the Architect refuses to do so without completing the plan he has started. Then comes the Union Leader who informs us about the death of a construction worker and asks the Architect to do something for them, while the Architect tells the Journalist to introduce this topic on television and the Journalist invites the Union Leader to speak. The Union Leader's only criticism of the devastated city is based on the fact that he was once a patriot, and that construction materials were coming from Serbia, from those who burned our houses and our villages. The Architect calls for patience, because there is a hope that his plan will be approved by the Municipal Assembly. To institutionalize the demolition of the city and to give colour to this issue, the UN administration appears in the form of a representative of the administration, Pierre, who organizes a party ostensibly to celebrate the successes of the city. After this party, there are some quarrels about construction, but the businessman's reasoning is that those constructions will be stopped and now a plan will be worked on, to create the "City of the Sun" and that all other plans can stop. So Pierre suggests he can stop all the evil in this city, but he is also an accomplice with the heads of the mafia, who are ruining the city in order to raise their capital. The Architect's daughter (played by Verona Koxha) has been hired by the UN as a translator and is being offered an opportunity by Pierre to go abroad, to France. She suffers from epilepsy and the anxiety of abandoning her father, but Pierre insists that she takes the job and vows to help them through the French ambassador. The voice of the Lord of Construction murmurs through the city at night, rejoicing in the sleep of the citizens and the darkness because in this way he can build his multi-storey buildings. In Pierre's office, Meti talks to him about the misfortunes of the people and mentions the war. Pierre hates this word; he closes his ears and will not hear about these sufferings, and so he fulfils the role of almost every UN administrator in Kosovo. In the second season of Neziraj's play, things take an ironic turn as the discussion of the urban plan and the voting have been removed from the agenda. There is a neo-colonial logic to the Administrator, who deletes things from the agenda and keeps his eyes closed in front of regular urban plans for the city, but his open eyes on the mafia who constantly build without any order and ethics. It is a familiar logic, one that has not stopped since the post-war period in Kosovo and has often been supported from above, when we were in the protectorate and in government, as now. At a meeting in the office of the Union Leader, the Architect's daughter enters and gives the father a letter in which she has received a threat. Pierre has informed the daughter to tell the father that he is not the only one being threatened, his daughter is too. The office is talking about organizing a revolt, a protest of workers, and for this the Union Leader has big promises. He says that he will bring together about 10,000 (or maybe at least 100 people). But, these are all empty words and the Architect remains stoic in his attitudes to save the city. He dreams that his daughter is being raped and runs to save her, but this is a result of his subconscious and his fear of threats that are constantly blurred by the mafia. He does not give up; he fights even in his dreams. He is a true dreamer. On the TV show, the Architect calls the UN, swindlers, mobsters and construction mafias, gangsters who are eating the city, and he calls the people who work for them mercenaries. He also raises the dilemma of what is the difference between the mafia and the UN, and says with a laugh that the mafia is better organized than the UN. When the show airs, it turns out that the interview with the Architect has been deleted and the Union Leader and Meti are working together. Everyone is turning against the Architect, perhaps because he alone had proposals and concrete work and ideas for the city, the others had empty words and played the role of agitator just to discover his plan. At night on the street, the architect is attacked. Smajli plays the role so well you can feel his passion, his love for the city. The Architect has connected his life with his city, and as a result he is killed by the mafia: the master of construction. In the last moments of his life, he asks "why do you want to kill me"? while Smajli's eyes convey the full spark of his ideals and love for the city. And the lord of constructions answers: because you have become the enemy of the development of this city. The play's ironical climax sees Pierre announce to the Architect's daughter two pieces of news, good and bad. Koxha's expresses her pain so well that in this scene it seems that a part of her body is resting with her father, and it is not too late for the scholarship she has won. Her eyes reflect this endless pain as she faints. But no, this is not the end. The final irony is when the killers and instigators inaugurate the 'Architect's Way', a street formerly known as the 'French Revolution'. The Architect's daughter makes her way to the airport, but still has questions for herself. Her father's murder leaves scars. She says that every autumn someone leaves and that she should have done the same, but now it is too late to leave, but not too late to stay and understand more about her father's murder. Here Pierre is embarrassed and starts talking defensively about how we internationals brought you freedom and you were waiting for us with flowers. The Architect's daughter had to stay to understand more the truth of this city and if she left she would never find out. The play's fifth and final scene - or season - connects the subconscious mind of the Architect's daughter with her father. When the Architect, in the middle of her dream, asks her `"are you happy?" `She answers hesitantly because she no longer even knows what she is; there are many people around her but she feels lonely. In Neziraj's drama we are presented not only with the absence of the father, but of the man, a man with dreamless dreams, who had decided to open his eyes to his daughter and his community. To imagine something better than dust, concrete and a waste of time, a system run by rotten people with rotten ideas. And when the rot spreads it led the best people of the city to be declared 'Enemies of the People,' and only after their murder to be declared heroes, with streets named after them, living on in myth. Traces of the beauty of a place are usually engraved only on street names and in the vivid traces hidden beneath the constructions. I shared the sense of disgust that permeates the play and I empathised with the Architect, with his loneliness during this process. The play also introduces the idea of the eye as an organ through which art sculpts our individual instincts. This is the privilege of some wise people, and we are desperately searching for them. As the crazy craving for making money becomes a goal in itself, it has undoubtedly weakened people’s capacity to understand the deepest potentials of life. And so as Bauhaus teaches us, the Architect displays a vision where he learns the special language of form in order to be able to give visual expression to his ideas. He conducts intensive studies in order to rediscover the grammar of design, in order to equip the spectator with objective knowledge of optical facts such as proportion, optical illusions and colours. He constantly informs us that art is a product of human desire, that it transcends the boundaries of logic and reason. It is an area of common interest for us all, like beauty which is an essential requirement of civilization and not simply multi-storey design. As his eyes after death are directed even more powerfully towards the public and after he is declared an ``enemy`` of development and the people, he tells us the opposite: we must fight for development, for our ideals. As in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche's On War and Warriors, he says that our highest ideal should be left to command us and that man is something to be overcome, and the love of life should be the love of your highest hope. In Neziraj's In Five Seasons, this is love - and hope - for the city. Author: Jeton Neziraj//Director: Blerta Neziraj//Cast: Egzona Ademi, Shpetim Selmani, Afrim Mucaj, Verona Koxha, Kushtrim Qerimi and Armend Smajli Naten, Ma, Metropol Theater, Tirana, Albania

Fatlinda Daku This is is not a typical performance. This audience is seated in a circle on the stage. In the middle of the circle sits Telma, an elderly woman watching TV. The play is set in her kitchen, a space surrounded with black walls. Some red pillows are on the chairs contrast with the gloom that grips the whole space. It’s been two minutes since the performance started. Everything seems normal. Routine. A scene of ordinary life. We wait for something to happen. All of a sudden, Jessi, Telma's daughter, enters the room. With an unusual calmness she asks her mother where her father's pistol is because she has decided to kill herself. Telma is shocked. She strongly opposes Jessie's decision. She tries to convince Jessie to not do it. We learn that Jessie is divorced and she has a son. She feels that she failed as a mother and the only way to make everything better is by killing herself. Suddenly, the set disappears. Don’t get me wrong, it's still there. But Telma and Jessie are the ‘play’ now. The whole of Ema Andrea's production is focused on the complexity of their mother-daughter relationship as portrayed by Ilire Vinca and Jonida Beqo. They face each other for the first time. They are talking about things they have never talked about before. Their dialogue is like a poem that never ends. Even the melody playing in the background ends up being unfinished. They tell each other white lies. They discover others. The harsh reality of their life is being told. As it is. They question one another, they confront their realities. The performance, based on the Pulitzer-winning play by Marsha Norman, raises many questions. Do we all experience a situation in the same way? What happens when there is no proper communication between people? What exactly is proper communication? And most importantly, do we lie to save other people from the pain or do we lie to save ourselves from the other people's pain? Natën, Ma provoked feelings in me. It made me reflect on myself and my circle. We all know a Telma and a Jessie in our lives. Often even we are like them in different situations. Like Telma who is afraid of the unknown, Telma who often lies to not hurt others with the truth, who likes her comfort zone and finds peace when she knows what will always happen. Even if it's all a white lie. The TV is a metaphor for this. Like Jessi who feels that she has failed in everything, in every role that this society has given her, as a daughter, as a woman, as a mother. She feels insecure. She feels rejected. Society has placed unattainable expectations on her. This wish to kill herself is her act of rebellion against those expectations. Jessi only exists, she does not live… Norman's play also makes you analyze yourself. Your actions. When the performance ends you suddenly find yourself questioning many decisions in your life. You find yourself thinking about the future and the way how you will communicate with your family and friends. You also count your own white lies. It is a play capable of making you become a better person. And I believe that this is the greatest achievement of any performance in the theatre. To make you have these ‘’a-ha moments’’. To make you, be you. Without the white (or not so white) lies. Author: Marsha Norman // Directed by: Ema Andrea // Cast: Ilire Vinca, Jonida Beqo // Music: Bojken Lako // Music Players: Endi Aaron Cekani, Rei Kondakciu // Stage Design: Enio Shehi  Arturo Ui, National Theatre of Kosovo Tringë Arifi Violence in the city. Violence in the people. This is the plan of gangster Arturo Ui, who in addition to a character in a play by Bertolt Brecht, is a character of our times, our politicians and those who govern us. Emptiness and decay manifest themselves in a moment when things do not go as expected by Arturo and his gang, slowly emerging into chaos. There is a lot of symbolism in the production, the last to be directed by the late Bekim Lumi. A scene in a bathroom, in which men sit on the toilet bowl sipping espresso, symbolises their comfort. This is followed by the complaints from the minority to the majority (the people) where they say `` why are they complaining`` ;`` why do you see crisis and why are the people not giving the cauliflower products while they are rotting? `` … They are sitting comfortably over the rot and misery they have created, trading in cauliflower then passing on complaints about not selling them. When some of his friends start to complain, to get out of that kind of comfort, Arturo's circle is narrowed further. The boss appears in the bathtub and two men scurry around him, then one comes and kills the other in front of Arturo - perhaps this scene shows the inferiority they have towards him, the will to commit more and more crimes to keep Arturo happy as he becomes the highest in the hierarchy of crime. After this macabre scene of murder disguised as suicide, the mafia talks about the corruption, while the old man appears as a business intermediary who is threatened. The whole scene is accompanied by music. Tom Waits' November is used in the face of crime, like Beethoven's 9th symphony with which the Nazis had committed crimes against humanity, and so they sing and dance like crazy people. As violence echoes across the city and humanity, Arturo devises another plan to destroy the courts in which the perpetrators are supposed to face justice. The culmination of the crime comes when his friends have become worried about Arturo as he comes second and kills the two friends who were in trouble for him. He is afraid of his own being. The old man addresses Arturo about the glory. He says that it is not won by force - and so the old man is also killed. Corpses appear in bathtubs. The first corpse is unveiled and resurrected. He rises and gives a speech: "You killed yourself when you killed me." Then the unconscious man begins to talk about violence, robbery and murder. He talks about the faith, about the will of the old man, the thanks he gave him in the will - though we do not see the will. When Arturo asks for votes on who is in his favour, he says those who are not in favour are necessarily against me. His only two remaining friends raise the hands of the dead from the grave as if they were voting, saying that everyone should be thankful. The irony is that only the two are alive and can vote, but his unjustifiable desire for power and crime makes them his two remaining friends lie and deceive him with votes, just as he likes to constantly lie to himself. Arturo appears again with an ironic speech about peace, protection of the city and trade, in which he says that no slander will stop him and he laughs like a madman. This laugh comes from not facing oneself, fear of oneself, a conclusion that drives him crazy. This is how the fate of a people ends and the scene closes without seeing the fate of this leader, but the being and the destruction towards this being are very well illustrated. The actors bring subtlety to their roles, an interiority is evident in every performance. Bujar Ahmeti, an actor of the new generation performs with the skill of a veteran. He takes the audience with him, walking us through the devilish mind of the character. Afrim Kasapolli, an actor of the older generation plays Dogsborough. He uses his interior a lot and masters the stage. The actors work well as an ensemble, as a team, clearly confident in the director and the concept. They fuse together. They become one. They evoke the passion, courage, and emotion of the characters, delicately drawing the relationships between the characters throughout the show. Author: Bertolt Brecht// Director: Bekim Lumi//Ass. director: Bashkim Ramadani // Cast: Bujar Ahmeti, Afrim Kasapolli, Afrim Mucaj, Labinot Raci, Faris Berisha, Valmir Krasniqi, Edon Shileku, Ismet Azemi, Ylber Bardhi, Kushtrim Qerimi, Shpetim Kastrati, Muhamed Arifi, Alban Rexhaj // Choreography: Majlajdo Gala // Music: Dren Suldashi // Stage Design: Mentor Berisha // Costumes: Alma Krasniqi // Tailor: Fadil Sahiti // Light Design: Mursel Bekteshi // Sound Design: Dren Suldashi, Avdi Gervalla // Stage Manager: Bajram Mehmetaj // Translation into Albanian: Robert Shvarc // Adaption into Gheg: Gazmend Berlajolli, Bekim Lumi // Organizer: Beqir Beqiri // Master Carpenter: Aziz Maloku // Carpenters: Rrahman Mehmeti, Hasan Buzaku, Fatmir Avdiu // Props: Xhemail Gllavica, Driton Musliu // Dressers: Fahredin Ahmeti, Linda Ahmeti // Make Up: Flori Hasani, Myrvete Tahiri  Balava, Theater Oda Agnesa Mehanolli What can two generations of women in the absence of men offer us on the stage? Dunja Matic's Balava wove together isolation and desire for freedom; courage and fear, love and dissatisfaction. The plot was a complex one. A mother of two daughters tries to keep them to herself by projecting on to them her own insecurities, vulnerability and the need to be loved and needed. She holds the ropes of the story. Her past has created a hole inside her that now seems to be filled only when she is accompanied by the only ones left that can ever love her. Played by Mirjana Karanović, the role was well-executed, a woman undefeated against a tragic fate, against the cold loneliness and against the big challenge of being a single mother. The formal dress, the hair fixed for a special evening, the posture, the way she talked, all these were perfect for the role. It was a performance of energy and commitment. Her sister, Tetka, played by Jasna Đuričić, was a character scarred by her own tragedy, who tries her best to reflect a spirit of joy and tranquility for her and the girls. She is the one trying to keep a level of normality until she will be the one that breaks down. The actress wore a spring dress, her hair fixed loosely and her careless body movements, that radiated warmth, were entirely different from her co-actress. All these differences only made the actress’s elegance more needed in the stage. The daughters, total opposites of each other, have different perspectives but the same purposes. One (Balava) desires to create happiness outside the house, with a Boy she met and the other, Babe, longs for a freedom far away from her suffocating mother, as a way to be happy. They try their best to get out of the house and live and enjoy their long lives; but Balava gets caught in an unexpected pregnancy and fears that the future she has created in her head is starting to fall apart. She experiences an unwanted abortion just when she made peace with wanting the baby, and despite her mother's claims of her to be an easy minded girl, she dares to confirm the opposite and run away from the house while trying to prove that she is the only one that can make the best decisions for herself. The actress Mina Obradovic represents a young character in the best supposed time of her life. She seems to have calculated all the right amount of joy, hope and saddens needed to intertwine in her character’s life. She performs with such an ease during the whole play, even in the most intense moments and is to be congratulated for her style of acting. The other daughter gets stuck there with her mother, and no matter how much she fights her and blames her for everything, she realizes that her is all she got, the same as she is all her mother got, that way she can't leave her alone and break her heart twice, after her father. Jovana Belović is careful to perform this character just as it is supposed to be performed; combining her father’s desire for freedom and her mother’s tendencies to be blocked. She was transparent, allowing us to see the wrecked world of the play’s character and she brought colour to the stage, to a world in which no colour exists. The set consisted of only four chairs lined side by side, showing a unity between the four of them, thus symbolizing that they have someone close even if they feel alone, that there is a space to be filled by them, even if the world is to small or to big to find them some place. The candle in front of them made me believe that in this house, there was some warmth, no matter how small. And however hidden, love is there, hope is still there and things will change, be that for good or just to make our characters understand that this all the best the universe can give them and maybe it’ s time to accept that. The dialogue flowed very smoothly. The jokes were delivered well, but sometimes the public (including me) laughed at them beforehand, since the subtitles were faster than the delivery. And that a shame, destroying the magic of these comic moments. But the real tragedy is the fact that all four of these women were closed in with so many walls, physically or mentally and none of them had the means to be free without losing a part of themselves. I was happy to have witnessed a play written by a woman, performed by women and visualized by a man, Andrej Nosov, as it demonstrates that the other sex has started to understand the female nature and its limitless capability to face the challenges and tragedies of a world that has only this to offer them. Author: Dunja Matić // Directed by: Andrej Nosov // Cast: Mirjana Karanović, Jasna Đuričić, Jovana Belović, Mina Obradovic // Composer: Draško Adžić // Stage Design and Costumes: Selena Orb // Stage Movement: Damijan Kecojevic  A.Y.L.A.N, City Theater of Gjilan Natasha Tripney The audience sit on the stage looking out a sea of empty seats. From this perspective they look like waves breaking on the shore. A rough red sea. Bodies flip flop across the seatbacks, storm tossed, both waving and drowning. Jeton Neziraj’s text takes the form of a minimal series of numbered micro-scenes, Brecht on espresso. It’s a slim play and, as such, a director’s playground. Blerta Neziraj takes this challenge and she runs with it. From this frame, she has woven an incredibly vivid and inventive piece about the plight of refugees forced to make perilous life-threatening sea crossings in search of safety. The play is ostensibly a comedy about Roccalumera, a Sicilian town where nothing of note ever happens. It’s starting to grind people down, the lack of action. Even the cat is depressed. A few refugees would at least liven things up, just like in Lampedusa. When they come across a body on the shore, they are ecstatic; even though, in all likelihood it is an Italian, they dress it up in a niqab. Blerta Neziraj takes what sounds, when spelled out like this, like the most caustic of comedies, as the inspiration for a series of incredibly striking stage pictures. Together with choreographer Gjergj Prevaz, she turns the inverted world of the theatre into a space of play and of dreams. The actors, dressed in funereal black suits, clamber across the empty seats; they stride from row to row. The rows of crimson seats become rolling surf, waves under which a body can sink. The lighting design by Yann Perregaux completes the transporting effect. He phosphoresces the theatre, plunging it into flickering darkness, creating an indoor storm. He pulls us down towards the seabed.

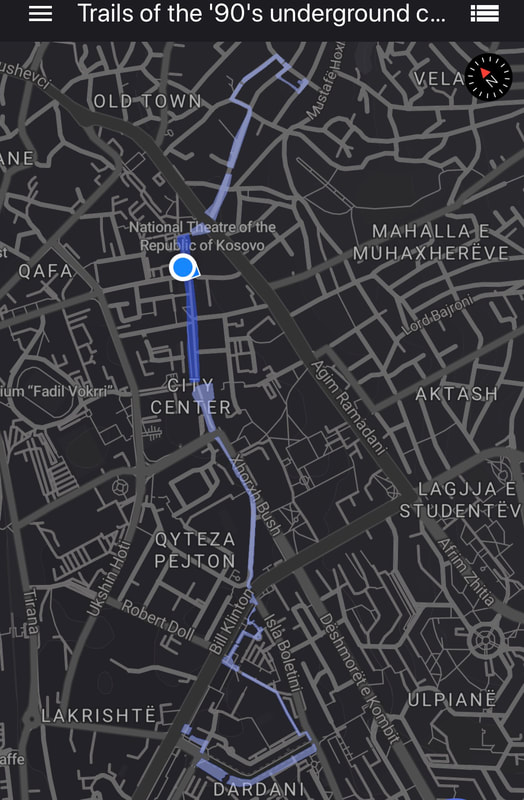

The cast work well together, whether zipping themselves into body bags or forming a chorus. Originally staged at the City Theater of Gjilan in 2019, the production was screened during the showcase due to the indisposition of one of the actors, but its power was not diminished. The way in which the space is used, with the actors and audience in opposite places, an inversion of the normal way of things, is the perfect representation of a world in which people fleeing warzones, people desperate enough to try and cross turbulent waters in a flimsy dinghy with their children in tow, are demonised, are seen as people to fear. Though less than an hour long, the production executes several deft tonal pivots, from comedy to horror and back again; only in the end does it slow down and unveil the image of Aylan Kurdi, a three year old boy, face down in the sand, dead. It confronts us with this image that briefly horrified the world but all too quickly became absorbed into the public imagination, one more picture at which to sigh and shake our heads. The last stretch of text is an act of re-humanisation, a poetic reminder that this is not just a powerful photo but someone’s child, a boy who once played and smiled, a life cut appallingly short. Author: Jeton Neziraj // Directed by: Blerta Neziraj // Ass. Director: Avni Shkodra // Cast: Aurita Agushi, Ernest Zymberi, Kushtrim Qerimi, Tringa Hasani, Gani Rrahmani dhe Alban Shahiqi // Stage Design and Costumes: Mentor Berisha // Choreography: Gjergj Prevazi // Music: Tomor Kuci // Stage Technicians: Mejdi Hoti, Haki Aliu, Fehmi Hoti // Organizer: Raif Haziri // Light Design: Yann Perregaux // Lightning Technician: Fatmir Halili // Sound: Florim Gagica // Props: Suad Berisha // Dresser: Bahrije Kurtalan Trails of the ‘90s Underground Culture - an audio walking tour Fatlinda Daku Everything starts in Dardania. And by everything, I literally mean everything. I have my iPhone and my earphones. I have downloaded the Echoes application. I am ready to listen. He lives on the 7th floor. He and his friends are playing outside. His mom stares through the window. Your mom does that too right? Or at least she used to do when you were young and went outside to play. Everything looks normal. He is eighteen and by the law, he is considered a grown up person. He has had his first sentish dance. He and his friends go to the pubs and talk and dance and enjoy the music. Just like I do, and you also. But this guy lives in 1998. And we are from 2020. In Kosovo. And there are two Serbian policemen who come sometimes and shout down the bars. The Albanian bars. They asked him one day if he would serve in the army. He responds that he will because it is his civil duty. That’s what others told him to say to them. I observe. I check my phone. I am being reminded to continue walking until I reach the end of the highlighted area. It’s a bit messy to figure out this application, but I am managing somehow. I look around. We are at Santea now, or as it was called on the 90s “Hani i dy Roberteve” A place when artists, journalists and philosophers used to meet and discuss everything, from Kosovo to Shakespeare. He has his Theatre Directing classes there. I keep walking with him inside the corridor. There was a protest by Albanians in the morning. Metallic things were flying around. He couldn’t finish his espresso. He had to go. It’s 24th March, 1999. They planned to meet with Adriana today. She was an actress, a good friend of his. With her mother they have arranged to go to Tetovo because it was safer there. We hear the noise of bullets. We learn that Adriana was killed inside this pub. I am sad. I think about Adriana while I keep walking through the highlighted area. I think of how many theater performances and films she would play in if she was alive today. I think of the contribution that she would give to the theater of Kosovo. As a woman, as an artist, as a hero of abnormal times. I keep walking. Now, he is talking about Nesha, a tall policeman, a Serbian guy. About the onion in his pocket during the protest. About the list. About the fact that he misses the main streets of Prishtina. About his first role in public space as a Serb. About his privilege of having a satellite television at home. About the Italian journalist who came to Prishtina and couldn’t believe his eyes. About Faruk Begolli, Enver Petrovci and his other professors. About many other things. I keep walking and listening to his stories.

The 90s are not black and white for me anymore. I think about how important these kinds of stories are. Personal ones. When young people were trying to be normal young people in abnormal times. I think about why there are not many stories like this being told to us. Why there is no recognition for these people as heroes too. Heroes of abnormal times. This was on my mind during the whole walk. I look at him now, at Florent. He is not eighteen anymore. It’s 2020. We just arrived at Theatre Dodona. The walk is over. A new theater show is about to begin… ‘You have discovered a perishable treasure, and it is imperative to share it with other people before it fades… ’ Irving Wardle

Over a five-day period, participants will attend workshops exploring the purpose of criticism – both as a space for analysis and debate, and a creative act – and the process of writing a theatre review. There will be the chance to discuss different critical approaches, style, structure, and form, as well as the changing role of the critic in an evolving media landscape. With the reduction of space for arts coverage in most mainstream media outlets, we will look at the practical realities and responsibilities of working as a critic today and discuss the benefits of a healthy and rigorous critical culture to Kosovo’s artists and audiences. |

Kosovo Theatre ReviewsReviews and creative responses to theatre productions in Kosovo Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed